When in 2019, in just the second lap of the Belgian round of the yearly Formula 2 event, a massive crash occurred around the Raidillon curve, one had no clue about the fatality that was to unfold.

Today, months later, we remember Hamilton’s shock reaction to the event, wherein he’s seen holding his head. Countless hits to YouTube have already been made.

Frankly, the eulogies haven’t really stopped ever since that fateful day at Spa. We recount all F1 drivers competing at Monza, the very next race, wearing black-armbands. And above all, we remember Charles Leclerc dedicating his win at Italy to the dear-friend he had lost.

Anthoine Hubert has reminded us about the fragility and vulnerability of F1.

But at approximately 51.7 miles (roughly about 83 kilometers) from Spa-Francorchamps, there stands Zolder, a track that has abandoned premier Grand Prix racing events.

It’s a track that was constructed actually as an alternative to the famous residence of the Belgian Grand Prix.

It’s a stern reminder about a haunting, that in all probability, F1 will never really forget.

A massive blow to our sport-loving consciousness about how really grim can the very sport we so dearly love be!

For 38 years back in time, precisely on May 8, 1982, it was here at Zolder where a crash consumed one of the best that the world of motorsports had seen.

A driver who was rated so highly, one that was primed for success and not to mention, billed for at least a world championship.

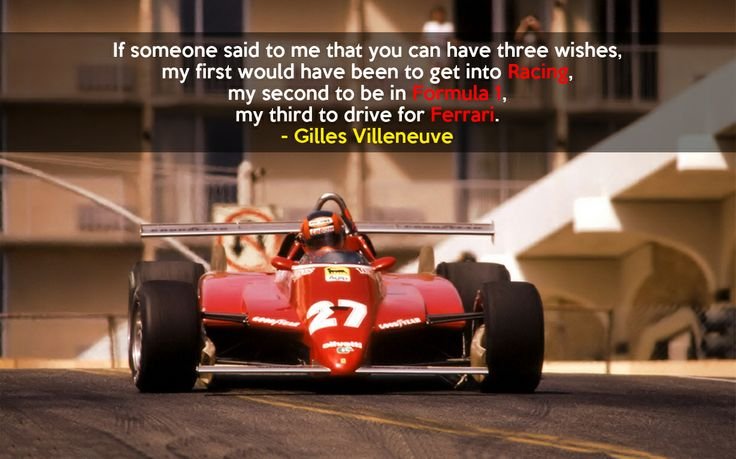

But sadly, Gilles Villeneuve’s career lasted only 5 years.

Putting the random math in a sentence puts forth a sentence that reads rather abject.

Which comes down to only half-a-decade spent in the most elite and highest form of Grand Prix racing called Formula 1.

What’s most sad about Gilles Villeneuve’s passing isn’t just that he was yet to win a world title or that he was going so well in his career, having driven for Ferrari.

In just 5 years of competing at the backbreaking world of F1, Gilles Villeneuve had already amassed 6 wins and 13 podiums from just 67 race starts.

But if you were to think about it, what hurts real bad is that Villeneuve was just 32 when he passed away, competing in the very sport he confessed he was born for.

But is that the only grief?

The very team he had dreamt of racing for, proved to be the one he was competing where he breathed his last.

Who can forget or forgive the Ferrari 126C, the Italian stable’s first attempt at a powerful turbo-charged car, suited to the ground effect aerodynamics?

Legend has it that, during the testing of the car, circa 1980 and later, in 1981 during another test at Italy, Gilles had issued with its handling.

A super-fast machine by Ferrari that, it is cited, was ideal for circuits with longer straits- Buenos Aires, Monza, and Hockenheim- the Quebec-born driver even famously called it a ‘big red Cadillac!’

Though none of that matters now.

Back then on May 8, what couldn’t have been sadder is the fact that Gilles Villeneuve wasn’t to enter the main Grand Prix event.

The dead-end would come during the qualifying, the unpredictable occurring with only 10 minutes left in the session as Gilles Villeneuve came to blows with Jochen Mass’ March, in a failed attempt to overtake the German.

Surely, while Mass, who cannot and is not blamed for the crash, had moved onto the right to let Villeneuve take through the racing line, the Ferrari driver only managed to contact the car in front and was left airborne, the collision occurring at an average speed of 120-140 mph.

Even at your bravest, you don’t even wish to imagine what it means to come in contact with a powerful Formula 1 car at speeds between 200-225 ks.

But here was a driver who had so much more to offer the sport that loved him back.

For someone whose big desire was to race for Ferrari, there’s a sense of gladness that, at least, Gilles was able to do that.

In fact, a year before curtains fell on a mercurial career, one that could’ve been of legendary proportions had it found a way to emerge unscathed from that dark day, Gilles Villeneuve claimed 1 pole position (at San Marino), set 1 fastest lap (same GP) and won two great contests with an iron-fisted dominance- at Monaco and Spain.

He was so quick that teammate Pironi, in the exact same machine, was no match, Villeneuve’s imperious Ferrari bettering a strong quartet of Alan Jones, Nelson Piquet, Alain Prost, and Carlos Reutemann in the 1981 season, emerging seventh to Pironi’s thirteenth.

What’s rather strange is that Gilles Villeneuve found a way to amass 25 points in ’81 despite 8 race-retirements, winning 2 races and securing another podium in the remainder of the contests.

Of course, back then there were no more than 15 Grands Prix.

Just imagine what might have happened had Villeneuve continued to race, competing well into the late eighties.

All the great battles Villeneuve would’ve loved to be a part of with the likes of Prost, who arrived aged 25 and Senna, who arrived only 2 years after the great Canadian’s passing?

It’s easy to rate someone when one is around in flesh and blood.

But when a ‘would-be’ icon falls, a legend rises.

And while it’s highly impractical to suggest how many wins or championships might he have bagged had the shamefully tiny sum of 5 years in Formula 1 been up to many more, what matters most is to focus one’s attention on what truly counts.

Truly speaking, in the passionate and quick driver’s ebb, there remained the great responsibility to usher F1 to its new heights, in the post-Niki Lauda and James Hunt era.

Remember when Villeneuve left us- aged just 32- Lauda, then 33, was driving in his twelfth season, with Hunt, 35, in his tenth season, while Peterson, 38, was already in his thirteenth season.

The experienced and legendary troika having already seen their best days, the onus was on a new quartet- featuring Nelson Piquet, Prost, Didier Pironi, and Scheckter.

But none commanded as much attention as respect as the legendary Gilles Villeneuve.

To this day and for time immemorial, Gilles Villeneuve will epitomize not just the thrills and ecstasy of competing at the highest annals at rip-roaring speeds.

But shall also serve a jolt courtesy possibly the biggest truth of them all. That at the end of it, motorsports are as much about chasing glories at ‘Godspeed’ as they’re about rabid uncertainty.