In the 1920s it became clear football was one of the very few things that bound the Argentina population, a nation of immigrants. Debates raged over newspaper columns of what the nature of Argentinian football should be and it emerged that it stood as the opposition to the game of the British, the colonial power of that era.

On the vast playing areas of British schools, football was about power and running but an Argentinian learned the game in the potreros, the small vacant areas of slums, on small, hard, crowded pitches where there was no teacher to step in if things got a bit rough and one needed to be streetwise and skilful to stand out amidst the din.

To describe a typical Argentinian football, El Gráfico’s editor Borocotó wrote in 1928:

“[He would be] a pibe [urchin] with a dirty face, a mane of hair rebelling against the comb; with intelligent, roving, trickster and persuasive eyes and a sparkling gaze that seem to hint at a picaresque laugh that does not quite manage to form on his mouth, full of small teeth that might be worn down through eating yesterday’s bread.

“His trousers are a few roughly sewn patches; his vest with Argentinian stripes, with a very low neck and with many holes eaten out by the invisible mice of use … His knees covered with the scabs of wounds disinfected by fate; barefoot or with shoes whose holes in the toes suggest they have been made through too much shooting. His stance must be characteristic; it must seem as if he is dribbling with a rag ball.”

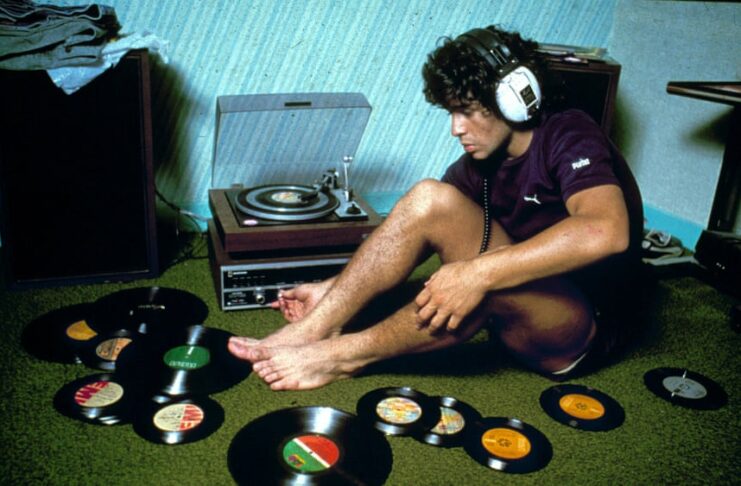

Just under half-a-century later Diego Maradona made his debut for Argentina as a 16-year-old and more or less fulfilled that prophecy.

Maradona grew up in extreme poverty in the potreros and that more or less shaped his football and his world vision. He neither had electricity nor running water while growing up and he sold all kinds of things to make money during his early years.

On the way to his school, he played keepie-ups with an orange or crumble newspaper, not letting it touch the ground even as he went over a railway bridge.

So gifted was Maradona that when he first went to the youth side of Argentinos Juniors, Los Cebollitas – the Little Onions, for a trial, the coaches thought he must be older than eight, but malnourished. After checking his ID, he was sent to the doctors and was put on a diet and pills in order to build him up for the rigours of professional football.

Almost immediately he became a phenomenon and by the age of 11, his name was getting mentioned in the national press. The weight of expectations and pharmaceutical enhancement were there from the start of his career.

So, too, was the tendency to indulge the child prodigy. It was apparent from an early age that rules didn’t apply for Maradona. His teachers gave him a passing grade for exams he missed.

He was a terrible loser and often found others to blame. He was immature and irresponsible and the weight of expectations from the media and the fans was already taking a toll.

Boca Juniors were labouring financially and to bail them out he played in a string of money-spinning friendlies. More injections followed to deal with the strain and the pressure became intolerable.

His cocaine abuse started at Barcelona, where he never fitted in. He was a happier soul at Napoli, where he took them to two league titles and the UEFA Cup. But even his spell in Italy was controversial and his virtuoso performances on the pitch came on the backdrop of allegations of drug abuse and his close relationship with the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia.

Maradona kept breaking rules, both on and off the pitch. His handball against England was first of three in high-profile games: he won a penalty after handling the ball in the 1989 UEFA Cup final and cleared off the line with his hand against the USSR in the 1990 World Cup.

The use of a plastic penis and a fake bladder with someone else’s urine to evade drug testers is already the stuff of legends. His tax affairs dominated headlines long after he left Italy as well.

Eventually, in March 1991, he tested positive for cocaine and banned for 15 months. He put on weight, had unsatisfying spells at Sevilla and Newell’s Old Boys. But once he announced that he wanted to play in the 1994 World Cup, he welcomed back with open arms.

Maradona cannot be treated by ordinary standards. He was not merely a genius football but he represented something to the Argentinian people.

He might have had four to five good seasons in his entire career, it didn’t have the relentlessness of modern greats such a Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo but that doesn’t matter to the Maradona legend. His success was borne out of his internal struggles. Maradona the player wowed crowds on the pitch despite Maradona the man off the pitch.

His performances in 1986 remain the single greatest individual feat in a World Cup. He didn’t just score goals, he didn’t just score brilliant goals but he played the game of the potreros on football’s grandest stage and won the World Cup playing that rustic brand of football. The icing on the cake was the fact he beat England on the way to glory.

Maradona remained a messianic figure in Argentina even after his career ended. A particular reverence was shown towards his views on various subjects, which he often doled out. He was credited with powers far beyond any mortal and that’s why, without any prior coaching experience, he was handed the charge of the national team in the 2010 World Cup.

It is why there is a church of Maradona in Buenos Aires. His fake penis was put on display at a museum in Buenos Aires as a religious relic, which was subsequently stolen during a national tour.

His career more or less ended after he tested positive for drugs during the 1994 World Cup. He did come back for two uninspiring seasons but 1994 was the true end, not only of a great career but a symbol of Argentinian pride.

Also Read: Nobby and Bobby – A Manchester United friendship for the ages